Every time I travel by bike (and every holiday season, when meat and egg-y things and cheesy appetizers suddenly become even more supremely important to people), I’m reminded of how thankful my little vegan self is to have nothing to do with the livestock industry.

Deep breath: I try really hard not to be one of those smug windbags who just can’t wait to talk to you about why her food choices are so gosh-darn wholesome, and I know that different people with different values and different information will make different choices. My choices aren’t necessarily the best for everyone, though without being too full of myself IÂ do think that many people who think deeply about it will come to conclusions similar to mine. Like I said, every time I take a bike trip and am intimately reminded of the ecological, biological, and public health implications of raising livestock, I’m thankful all over again for my colorful and delicious plant-based diet.

(gratuitous vegan food picture;)

(gratuitous vegan food picture;)

Take my last excursion through rural Oregon and Idaho (or even the trip before that through southern Utah). Much of what I biked through was BLM land — that is, land that’s regulated by the Bureau of Land Management, an agency that’s supposed to “sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of America’s public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.”

The emphasis there is mine. Miles and miles and miles of public land I biked through, every single inch of it fenced off and unavailable. Why? Because it’s leased out to ranchers, who pay a pittance to use public land to fatten their cows, cows that run rampant, cows that trample and pollute the streams, cows that chow down the native vegetation, more cows than the land can healthily support, cows for days pooping all over the streams that you and I can’t get to even if we wanted to anymore, because it’s more important to subsidize cattle.

If you’ve ever traveled between grazed land and protected land, you know what I’m talking about. The contrast is stark: one minute there are trees, a plethora of different and differently-sized shrubs, a variety of animal life, riverbanks covered in erosion-withholding plants — in short, biodiversity, a healthy ecosystem — and the next minute, there’s nothing. Riverbanks are bare and trampled, more quicksand than bank; the water is full of algae; the ground is flattened, empty but for cow pies. In Utah, this manifested as miles and miles of dust and tumbleweeds which, though an icon of the American West, are actually an invasive plant that replace the native grasses and forbs that hold the land and topsoil together. (And ironically, the livestock that graze down the plants, inviting the takeover of tumbleweed, mostly can’t eat the tumbleweeds that move in.)

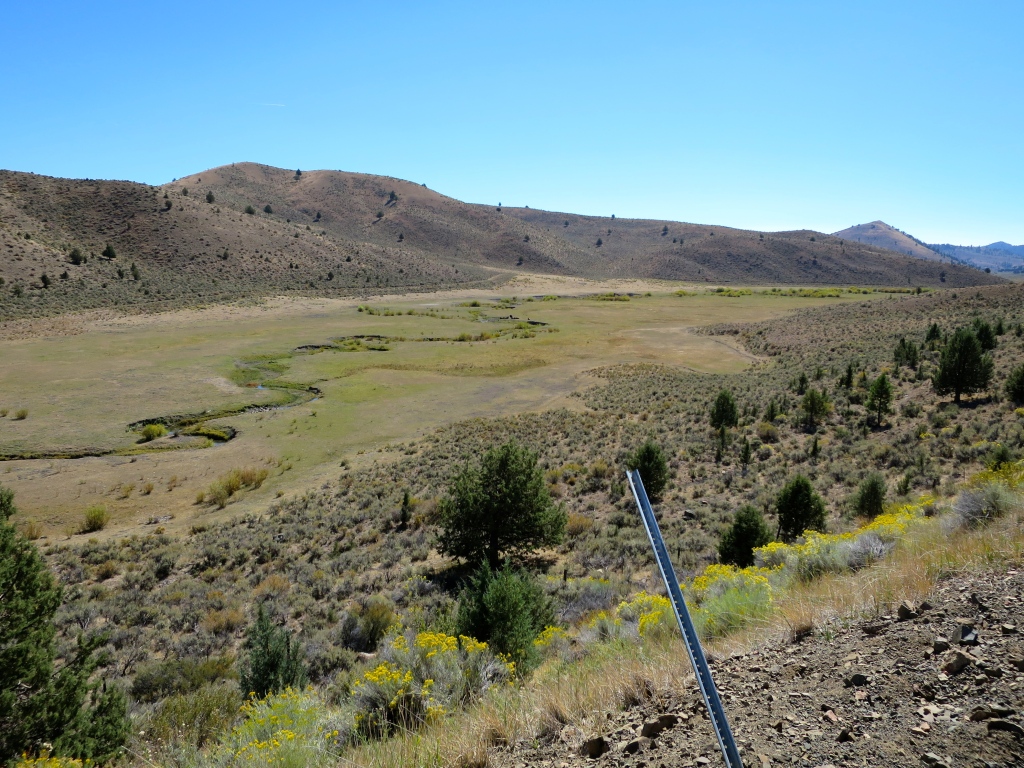

(can you tell which part of this landscape is used by cows? Of course you can)

(can you tell which part of this landscape is used by cows? Of course you can)

I know, grazing doesn’t always have to result in this, but when you can get more money for having more cows, health of the land — public land — takes a backseat to bottom line. It seems.

It’s not just beef, of course. If you’ve ever biked past a dairy you know they have their own breed of disgusting: that sour, rancid smell, a smell wrought mostly of the giant cesspools of manure that that many cows in one confined space create. One article I read recently mentioned that the manure from 200 milking cows produces as much nitrogen as sewage from a community of 5,000 to 10,000 people. And that doesn’t even begin to get into the sheer amount of methane produced, or the number of antibiotics, hormones, and other pollutants that inevitably find their way into our groundwater from dairy overflow.

(nothing like hordes of fragrant cows crammed together near their manure lagoon to make me want to eat things made with milk!)

(nothing like hordes of fragrant cows crammed together near their manure lagoon to make me want to eat things made with milk!)

When you live in a city, away from where all this land use goes down, it’s easy to just buy your package of wrapped-up, looks-nothing-like-an-animal meat, or your quart of milk, or your baby loaf of cheese. You can even feel good about yourself: it’s organic! It comes from a small farm! It’s free-range! And sure, some options are certainly better than others. But you know what? After so many bike trips through this stuff, after miles and miles of seeing the aftermath of livestock on the land, I’m happy to entirely opt out. There is so much delicious food to eat that doesn’t require this sort of ecological devastation.

But stasia, don’t other crops, even crops that have nothing to do with animal production, also have impact on the world? Certainly. We could certainly get into all sorts of discussions about destroying the Amazon to grow soybeans or coffee (although 91% of the land in the Amazon that was deforested since 1970 is now pasture land), or the ecological implications of our dependence on wheat. Deciding to not eat meat or dairy certainly isn’t the only decision to make. If you live in this world, you have to be prepared to have a certain amount of impact on it, but I’m all about reducing that impact. And the most resource-efficient way to do that in terms of diet is to eat vegan.

There are stats all over the internet as to how much more ecologically friendly a plant-based diet is. Even the meat eater’s guide concedes that if everyone in the US ate no meat or cheese just one day a week, it would be like not driving 91 billion miles, or taking 7.6 million cars off the road. That’s not even asking you to stop eating meat or dairy altogether, just not eat it one day a week.

Plus, it might be worth putting in perspective: one pound of beef takes 2000 or more gallons of water to produce (as opposed to, say, 34 gallons for a pound of potatoes). And while 40% of all arable land on this planet is used to produce food for the 7 billion of us who live here, 30% — fully 3/4 of the land that’s used to produce food — goes into the production of meat. That’s not even the production of eggs, milk, or other byproducts, but full-on meat. And most of that meat feeds not the hungry of the world but Americans, the average of whom eat a whopping 271 pounds of it a year. (An average Bangladeshi eats just 4 pounds, to add some more perspective.)

Wouldn’t it be lovely if we could take a step back from all that and say, hey, we’re Americans, but we don’t actually have to cram our faces full of all this meat — all this food that’s linked to obesity, heart disease, high cholesterol, chronic disease? That we don’t actually have to use all this land to grow meat when creating a calorie of meat takes 10-15 times as much fossil fuel energy as creating one calorie of plant protein? Wouldn’t it be lovely to be able to say hey, I’m an American, and as a global citizen, I’m concerned about the way our planet’s resources are being used, and I want to be able to feed everyone, not just myself and my family? Wouldn’t that be nice?

Anyway, I could go on and on, and teasing out all the various nuances and implications of every study ever conducted could start a conversation that goes on for days. For anyone who wants a cliff-notes version, I’d suggest this compilation of numbers about meat-based, vegetarian, and vegan diets. I think it’s worth thinking about. For realz. It’s a cop-out to just eat the way you’re used to, unthinkingly, just as it’s a cop-out to go through the world and make any decisions unthinkingly. Come on. Give it some thought. And push my thoughts. Figure out what the right thing to do is, and do it.

What about numbers? Humans, in some form or other, have been omnivores for … what, a million and a half years? I have trouble arguing against success. :-) For the last 6,000 years or so (a blink of an eye), since we settled down, we’ve had diabetes, stroke, heart disease….and breads, and grains, and other additives to our diet. If it ain’t broke, why try to fix it? Just fix how we raise our animals. Buy only pastured eggs and meat. Eat it once a week or less, like our ancestors. Lots of ways we can improve. But to try to improve on success seems…counter-productive.

Maybe it’s right that a diet with meat was good for people once upon a time. Probably people are even able to eat meat in a healthy way now if they’re super careful to avoid anything that was raised with hormones, crazy amounts of antibiotics, and the like. But we’re talking about two different things: 1) individual human health, and 2) health of a system, in this case, our planet.

We live in a world now with way more people than there were a million and a half (or even 200) years ago. And buying pastured meat doesn’t fix the fact that the animals out there pasturing are taking up more and more and more land — land that could be used much more efficiently if it were being used for something other than to grow meat — to feed our insatiable appetites.

So, sure, meat (and dairy) certainly aren’t the only thing that have made us unhealthy, but individual human health isn’t the only concern here. I’m also concerned about the health of our system (upon which our individual health ultimately rests, of course). And for our system, hands down, one of the biggest things we can do is stop eating so many animal products.

Im sure there are a lot of cows, pigs, chickens and fish that would agree with this. Humans are creatures of habits that are very hard to break, especially when we don’t put too much thought into why we have them. Swimming downstream is the easiest. But I agree, even though I am an omnivore. I don’t mind going without meat as much as possible. I have a lot of respect for folks who can live a socially disciplined life that benefits society, which really could not care less.

Yep – the key is in your last line: “stop eating so many animal products.” A little meat once a week or so, raised in a healthy system, is plenty. It’s all my father’s generation had. We’ve become a nation of excess. That’s where the problem lies.

Dierdre, I’m not sure what you mean by success. 6000 years ago an omnivore human’s average life was 30 years. I hope we’ve evolved since then. It only makes sense to reconsider “traditional” practices that are not wise.

I understand why somebody wants to be a vegetarian: religious superstitions, those who give up meat because of their concern for animals, those who believe in general health benefits and longevity of being a vegetarian, etc.

But why do you have to go vegan? The mankind throughout the whole history relied on

milk derived products. Would you put your growing infant on a dairy free diet? I doubt it.. Think about aboriginal peoples of northern territories in Canada or Russia, they simply can;t survive without meat and milk.

The problem is not in the cows and ranches you see on your bike tours, it is in the overpopulation and in the consumption spirit of modern society , there are too many of us and we need to be fed and satisfied. Think about this, if majority of people go vegan, then all these lands will be occupied by soy growing ( or other plants) instead, and the pollution of countless pesticides and other chemicals will be much worse, then cows, poops, which is by the way is perfectly harmless for the environment.

I would recommend to read the article below, this helps to establish a more balanced opinion about this topic

“How being vegetarian does more harm to the environment than eating meat”

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-1250532/Being-vegetarian-does-harm-environment-eating-meat.html

Hey Repoliator,

Thanks for the comment. You’re right that a large part of the problem stems from overpopulation and overconsumption, but given that this many people already live in the world, what are you suggesting? I doubt you actually mean that we should be culling the population… Certainly having fewer children (which I am all about) will help over time, but in the meantime, eating less meat and fewer animal products is one of the easiest viable options.

That article you link to is rather uncompelling. The basic argument is that processed meat substitutes have a greater impact on the environment than meat. Certainly processed food in any form has a large environmental impact (which is why I also avoid processed food), but remember that 30% of the land in the world is being used to produce meat. That leaves only 10% that’s raising the rest of everything else, including milk and anything else that goes into meat substitutes. So sure, processed meat substitutes aren’t the best answer, but they’re still a heck of a lot better than meat.

Finally, there’s a large difference between feeding an infant human breast milk and feeding a person milk that comes from a totally different species. There’s stuff all over the internet about that, so I’ll leave it to you to research that one.

I agree, much of the world and much of our history came from eating meat and milk. But in today’s global environment, I really don’t think it’s the best option anymore. I appreciate your providing alternate viewpoints, but I need a little more substance to change my beliefs here.

Note the trend in all these critical comments: most of them are citing tradition. “But, but, we’ve been eating meat for so long! My dad and grand-dad ate meat, and I wanna eat meat too! Stop telling me I’m a bad person for it!” Challenging the familiar, the comfortable makes people sooooooooo defensive! They’ll bite you! Ask people to, to the best of their abilities, live their lives in a way that reflects their values (most people’s would not kill an animal to eat it., so they pay someone else to do it), and they become angry… I shared your article on my facebook page; I know no one will read it. Sigh.

You’re totally right about changing the familiar. It’s hard to decide that something you’ve always done isn’t actually the right thing, and then even harder to change it.

Thanks for sharing anyway, even if you think no one will take note. You never know who’s actually paying attention, or what will make someone stop and think — maybe your Facebook page is the gamechanger for someone! :)